National Parks, Forests, Wildlife Refuges, and Other Lands: What's the Difference?

Four U.S. federal agencies manage lands in different ways for different uses.

[Note: I originally posted this on my old blog in 2017, but am resharing it here because it’s still relevant! I made a few small updates but otherwise left it as-is; message me if you think there’s anything else that needs updating.]

If you enjoy the great outdoors, you may have heard of many types of lands with “National” in the name. What do they all mean?

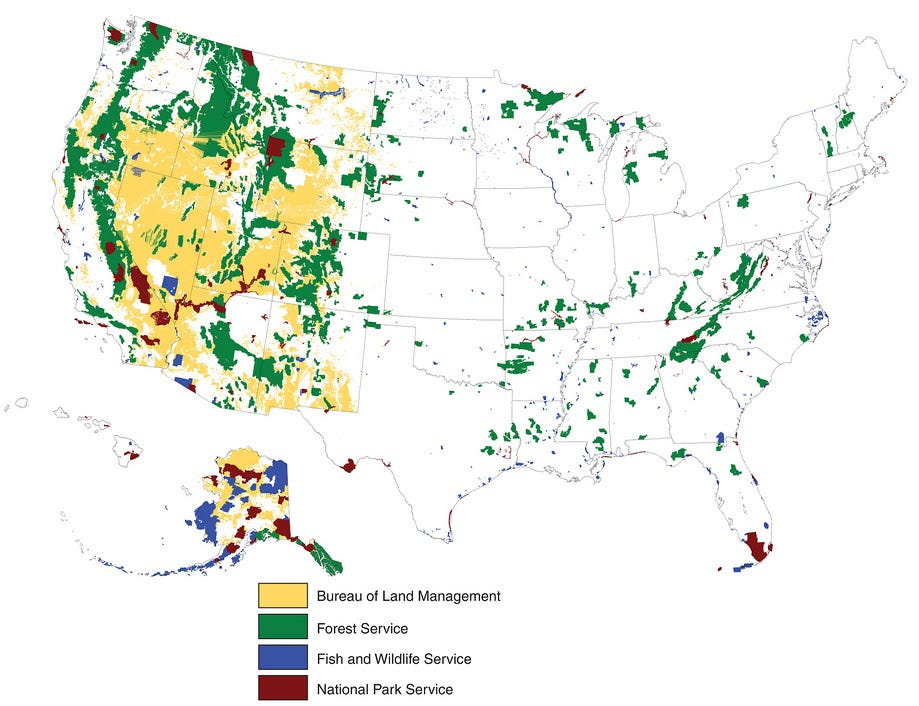

These designations can be traced to the four primary land-management agencies in the U.S. federal government: the Bureau of Land Management (managing 248 million acres), the U.S. Forest Service (193 m.a.), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (89 m.a.), and the National Park Service (80 m.a.). Note that while the National Park Service is the most famous, it actually manages the smallest amount of land.

The key distinction between these agencies is their mission:

The Park Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service both focus on a combination of resource preservation and compatible recreational uses. Park Service units in particular tend to have a lot of rules and restrictions, as well as more developed visitor facilities.

The Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management have a multiple-use mission: land is explicitly supposed to be used not only for conservation and recreation but also mining, oil and gas drilling, logging, cattle grazing, and renewable-energy production. These extractive uses are managed using sustainable-yield principles. These agencies also often allow a wider range of recreational uses, including hunting and off-road vehicle use.

All of the agencies are part of the U.S. Department of the Interior—except the Forest Service, which lies in the Department of Agriculture. Here’s a map of each agency’s land:

I will now discuss each agency’s lands in detail.

National Park Service (NPS)

The NPS manages the National Park System. Despite the name, this system is more than just the 63 “National Parks”—it has over 400 units with over 30 different designations.

National Parks and National Monuments are, for all intents and purposes, the same. They are the most restrictive; they usually ban resource extraction, off-road vehicle use, and sport hunting. Monuments tend to be smaller than Parks, but there’s a lot of variance. See my previous post for more detail on National Monuments.

Most National Recreation Areas either surround reservoirs (and focus on water-based recreation) or are located in urban areas. NRAs, National Preserves, National Seashores, National Lakeshores, National Rivers, and certain other units are similar to National Parks and National Monuments, but in some cases they have looser regulations. The NPS also manages many historical and cultural sites, but those are usually much smaller areas.

The units designated as National Parks are not considered by the NPS to be on a “higher tier” than other units—although in practice that’s how they’re perceived by the public. There is no “system” of 63 National Parks; rather, 63 units of the National Park System happen to carry the title National Park. Unit titles are given by Congress, and which ones are National Parks is intensely political.

About two-thirds of the NPS’s land lies in Alaska, although those parks get few visitors.

(Note that some National Monuments and National Recreation Areas are managed by other agencies; the descriptions above only apply to NPS-managed ones.)

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)

The FWS manages the National Wildlife Refuge System. Most units are designated as National Wildlife Refuges, but some go by other names, like the Patuxent Research Refuge and the National Elk Refuge.

National Wildlife Refuges are intended “for the protection and conservation of our Nation’s wildlife resources”—with a recognition that “wildlife-dependent recreational uses involving hunting, fishing, wildlife observation and photography, and environmental education and interpretation [are] the priority public uses of the Refuge System.” Extractive uses may be allowed if deemed compatible.

Most FWS land (86%) is located in Alaska. In the rest of the U.S., most refuges are located in wetlands.

U.S. Forest Service (USFS)

The USFS manages the National Forest System, which includes National Forests and National Grasslands. The USFS also has land designated as National Monuments and National Recreation Areas, but these are overlay designations on National Forests/Grasslands, not independent units (as is the case for the NPS). Each National Forest/Grassland is divided into ranger districts.

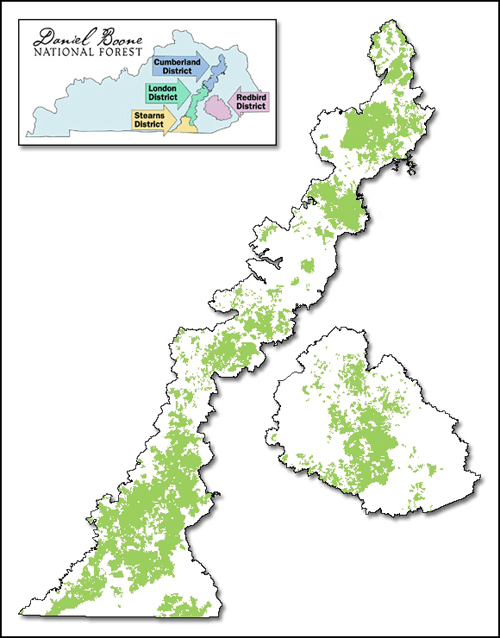

Each National Forest/Grassland has an authorized boundary within which the USFS is allowed to own and acquire land—key word: allowed. Significant amounts of private (or state-owned) land, called inholdings, exist within authorized forest boundaries; the USFS has little control over land use and activities in inholdings.

Because most National Forests/Grasslands were established when the West was sparsely settled, only 10% of the land in Western forests is inholdings. By contrast, forests in the East were established after widespread settlement, resulting in 46% of their land being inholdings.

The USFS is the only one of the four land-management agencies that owns a significant amount of land in the eastern U.S.

Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

The BLM manages the National System of Public Lands.

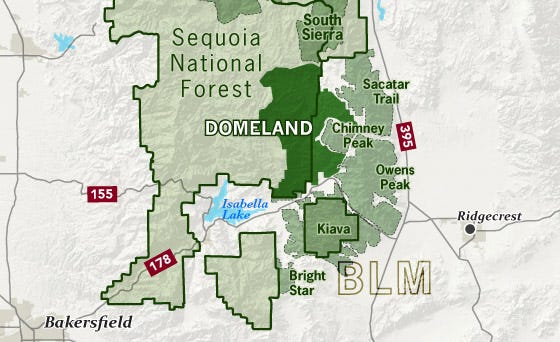

The very idea of land ownership and naming at the BLM is fundamentally different from the NPS, FWS, and FS. Generally speaking, the BLM doesn’t manage a collection of discrete, encapsulated, named units of land like the other agencies. Instead, it owns a bunch of land whose management is divided among a number of state offices (which are further subdivided into districts and field offices), and its ownership pattern is often more patchwork-y than that of the other agencies.

The basic notion that all BLM lands even constitute one “system” is quite new; the “National System of Public Lands” name was only created in 2008.

BLM land is often left off of maps. Here’s how Google Maps depicts Northwest Wyoming:

See that “blank” area in the center-right? Much of it is actually BLM land, including a number of off-the-beaten-path sights.

The other agencies are defined by land that was specifically set aside, but the BLM’s land is land that generally wasn’t—the “leftovers” that were inherited from the General Land Office. Federal policy used to focus on disposing of this land, but over time, the focus shifted away from disposing of federal lands and toward keeping them. This culminated with the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, which effectively ended homesteading.

As a result, much of the BLM’s land is desert, shrubland, and tundra, because areas with more hospitable climates and more water were more attractive for human settlement and agriculture or were more likely to be included in the National Forest System.

The BLM has a very clear two-tiered treatment of lands: while much of the BLM’s land is nameless and intended for multiple uses, the National Landscape Conservation System represents lands intended primarily for conservation and related uses. These are discrete, named units, with a variety of names, including: National Conservation Areas, National Monuments, Outstanding Natural Areas, Wilderness Areas, and Wilderness Study Areas. The BLM places a heavy public marketing focus on these lands, and these units generally have entrance signs.

In addition to the NLCS, the BLM does have some other named areas, including the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, Areas of Critical Environmental Concern, and a number of recreational areas. But otherwise, BLM land is generally anonymous. Most the BLM’s public-facing resources, like websites and social-media accounts, come from the state offices and not specific land units.

Almost all of the BLM’s land is in just 11 Western states. It also has broader authority to acquire and dispose of land than the other agencies.

Land designations that span agencies

There are some land designations that can apply to multiple agencies.

National Monuments can be managed by any of the agencies—and can even span multiple agencies. I wrote a detailed post about them. NPS monuments tend to have more restrictions than those managed by the BLM and USFS.

National Recreation Areas can be managed by the NPS or USFS (or in one case, BLM).

Wilderness Areas are part of the National Wilderness Preservation System and are generally undeveloped lands where the only activities allowed are non-motorized recreation and scientific research, and where human influence on the landscape is supposed to be unnoticeable. They require Congressional approval. Wilderness areas are overlay designations, and can span lands managed by multiple agencies. (The BLM has the authority to create Wilderness Study Areas, which carry similar protections to Wilderness and are intended to be temporary while officials study the area to determine whether or not to recommend it for permanent Wilderness protection.)

Finally, the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System and the National Trails System both feature management by multiple agencies.

Other random things to know

There are also a variety of marine areas under federal control/protection. These are managed by agencies including the FWS, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

Annual passes cover entrance and day-use fees not only at NPS units but also at those managed by the other agencies.

Smokey Bear is a product of the USFS, the Ad Council, and the National Association of State Foresters. It has nothing to do with the NPS.

NPS units tend to have more visitor information and maps available than lands managed by the other agencies. And the maps are much better, thanks to the people at the Harpers Ferry Center.

NPS units often have restrictions on dogs. USFS and BLM lands are a better bet for dog allowance.

Many portions of USFS and BLM land allow you to camp for free almost anywhere you want. There are also usually no entrance fees, just day-use fees at some recreation sites.

Just because the USFS and BLM have a multiple-use mission, that doesn’t literally mean that each piece of land does; different areas have different emphasized uses and sometimes different regulations.

The BLM also manages underground mineral rights for all federal lands, totaling about 700 million acres.

Land management is not the only activity of the land-management agencies. They all have other roles too.

Unless otherwise cited, most numbers in this post come from this Congressional Research Service report.

Also check out the Bureau of Reclamation and Army Corps of Engineers, which (among other things) maintain a number of dams and reservoirs that are surrounded by recreational lands—though those lands are often managed by other government agencies.