How Trying to Make Government Better Often Makes It Worse

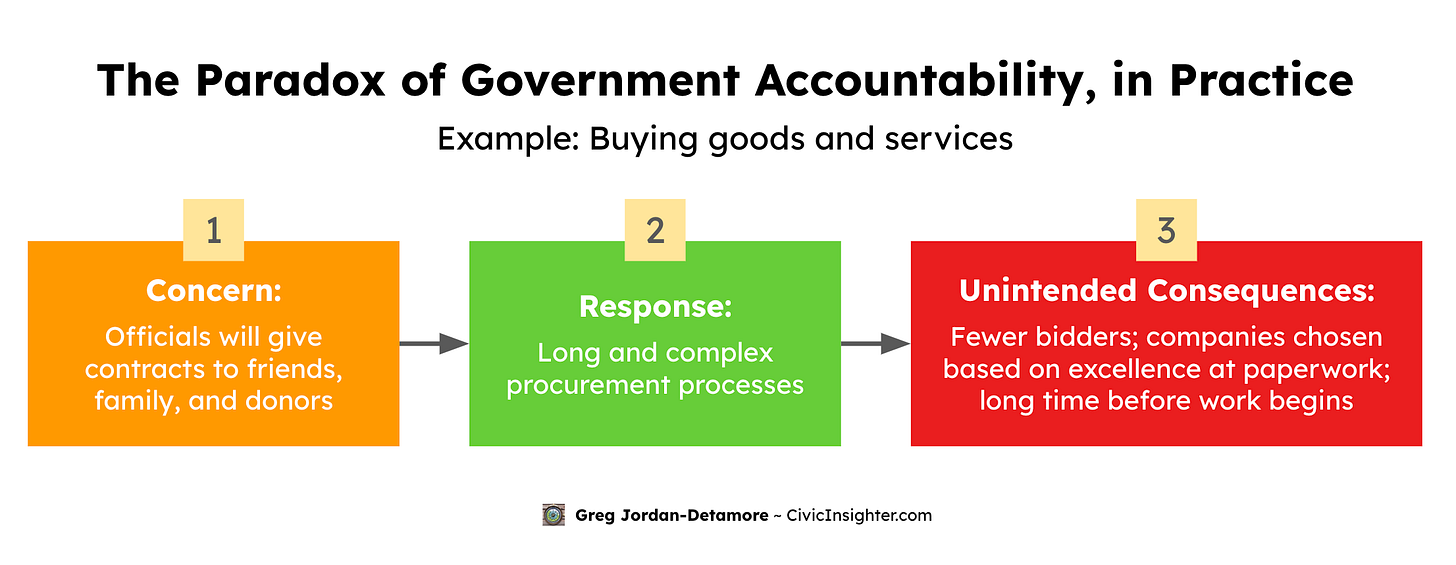

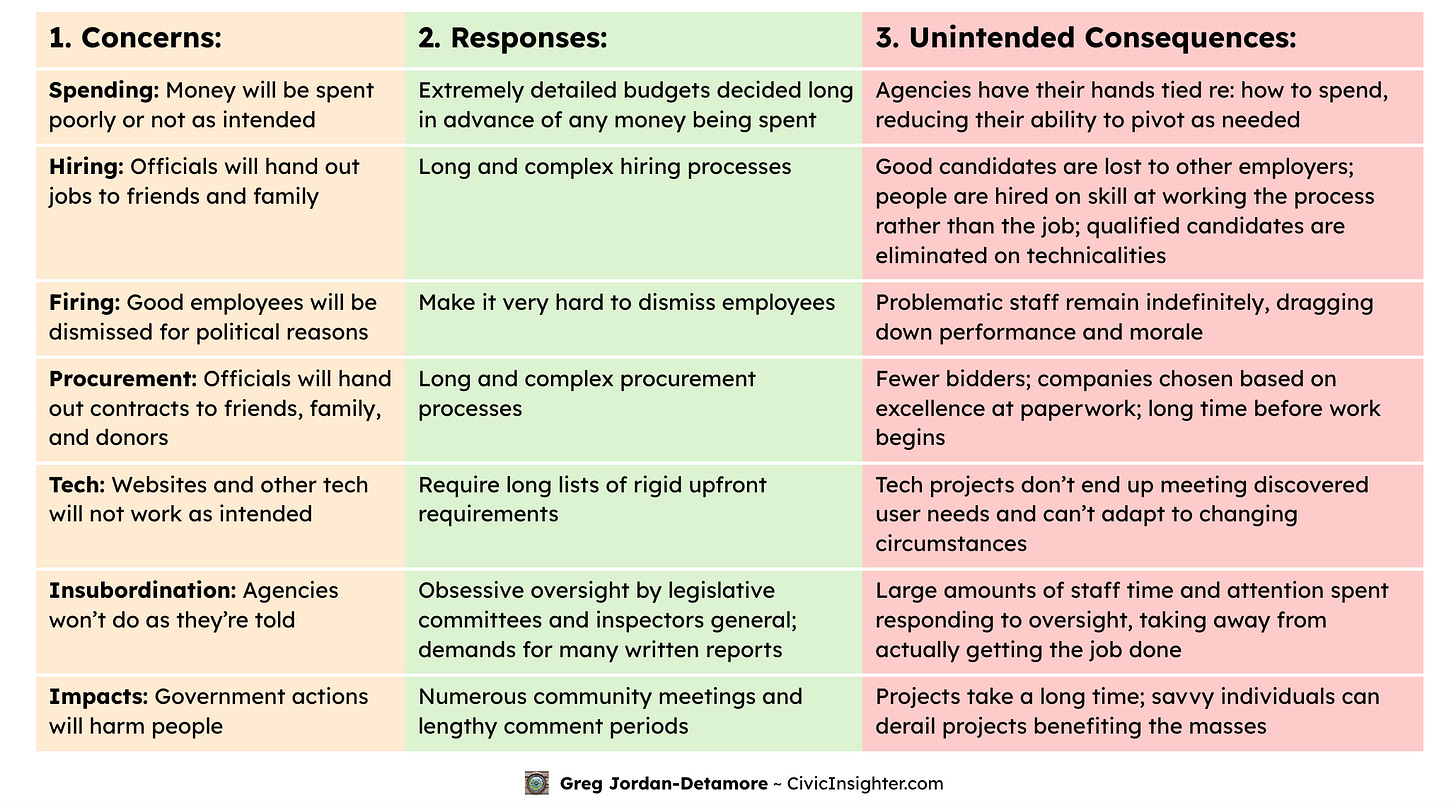

Fair concerns about corruption and effectiveness create loads of bureaucracy that impair government’s ability to deliver.

Throughout my career working with governments around the U.S. and elsewhere, I have repeatedly encountered what I now call the Paradox of Government Accountability: Many of the barriers to government efficiency and effectiveness are the result of protections put into place to ensure quality and guard against corruption.

Let’s see some examples.

Paved with good intentions

You wouldn’t want government staff handing out public contracts to their friends, would you? We should spend public money in the best way possible by awarding contracts to a company that will give us the best value for money, right?

Here’s how this gets put into practice. When large dollar amounts are involved, governments buy stuff through lengthy processes that often involve:

Specifying what they want to buy in great detail

Requiring potential bidders to fill out a mountain of paperwork, on which a single mistake or missed question can get your bid tossed in the trash

Having staff (some of whom may not be subject-matter experts) review the bids and choose a winner

Offering a chance for bidders who weren’t chosen to protest the decision

Eventually getting started with the work—months or even years after the process started!

As Jennifer Pahlka says in a podcast with Ezra Klein:

The paperwork required to bid on a major government project, whether it’s technology or anything else, is massive. There’s a lot to review. And there’s very little evidence of actual competency that [is] required in this paperwork. It’s all evidence of compliance.

The end result? Far too often, contractors are chosen who are experts at filling out paperwork but not at doing the real work, and sometimes even have a track record of failure.

Klein says:

I’m not saying this is their only competency—but across a bunch of these contractors, what they have is a competency in contracting. … They know how to work with the government, which is a huge pain. And this feels like another place where the procurement rules and the way different regulations, et cetera, have been interpreted, it’s really not what the legislature was trying to do.

We see this kind of pattern elsewhere too. Hiring is often a byzantine process that involves a ton of paperwork and takes many months, or even over a year, to complete. As Klein notes, “We’re so worried about patronage, we’re so worried about corruption, that we’ve made the whole thing work really poorly.”

Sometimes the unintended consequences are the literal concern that was trying to be addressed in the first place. With hiring and procurement, the mountains of paperwork—which otherwise serve as a barrier to entry—create an advantage for anyone with friends or family on the inside who can help coach them through everything.

Regarding tech, Mark Headd writes:

Our government was designed to make it harder to do things quickly and effectively. … And while this isn’t always the reason that government technology projects fail, it is a common reason why a project team might adopt suboptimal practices.

Here are a few more examples:

To be clear: We don’t always end up with the worst of these unintended consequences, and there are many challenges in government that have nothing to do with these issues. Still, these are very real issues.

Our competing priorities are the problem

As Nicholas Bagley writes in his essay The Procedure Fetish, “The laws that structure the American administrative state were built on a bedrock of distrust.”

The hard reality is this: Many of the reasons government has trouble being effective and efficient are our own fault—they’re responses to pressures that we ourselves, via our elected officials, have placed on the system. Any serious effort to improve service delivery and state capacity will require having tough conversations about trade-offs and priorities. Finding ways to help government actually deliver on its promise while still holding it accountable and preventing corruption is a devilishly difficult task.

Consider: It would be way easier for government to buy stuff if you could just give permission to buy whatever from whomever, and in fact this is often allowed for tiny purchases. But it’s pretty easy to see how this opens up enormous opportunity for corruption if you let millions of dollars be spent this way. This isn’t theoretical; corruption is a serious problem in many countries.

I sadly do not have a magic solution. But I do have some thoughts on possible remedies—and hope to share them in a future post. Subscribe now to hear about the exciting content I’ve got coming up.

I’d love to hear from you: What do you think? Do you see these problems in your work or your communities? How might we address them? Let me know in the comments, and share this post with your friends so we can bring them into the conversation!

It certainly is a specialized skill set to apply and win government contracts! What do you think about new practices like this: https://techfarhub.usds.gov/resources/learning-center/field-guides/tech-challenge-playbook/