U.S. Civics Education Has Two Blind Spots

Students—future voters—need to learn about local government and policy implementation.

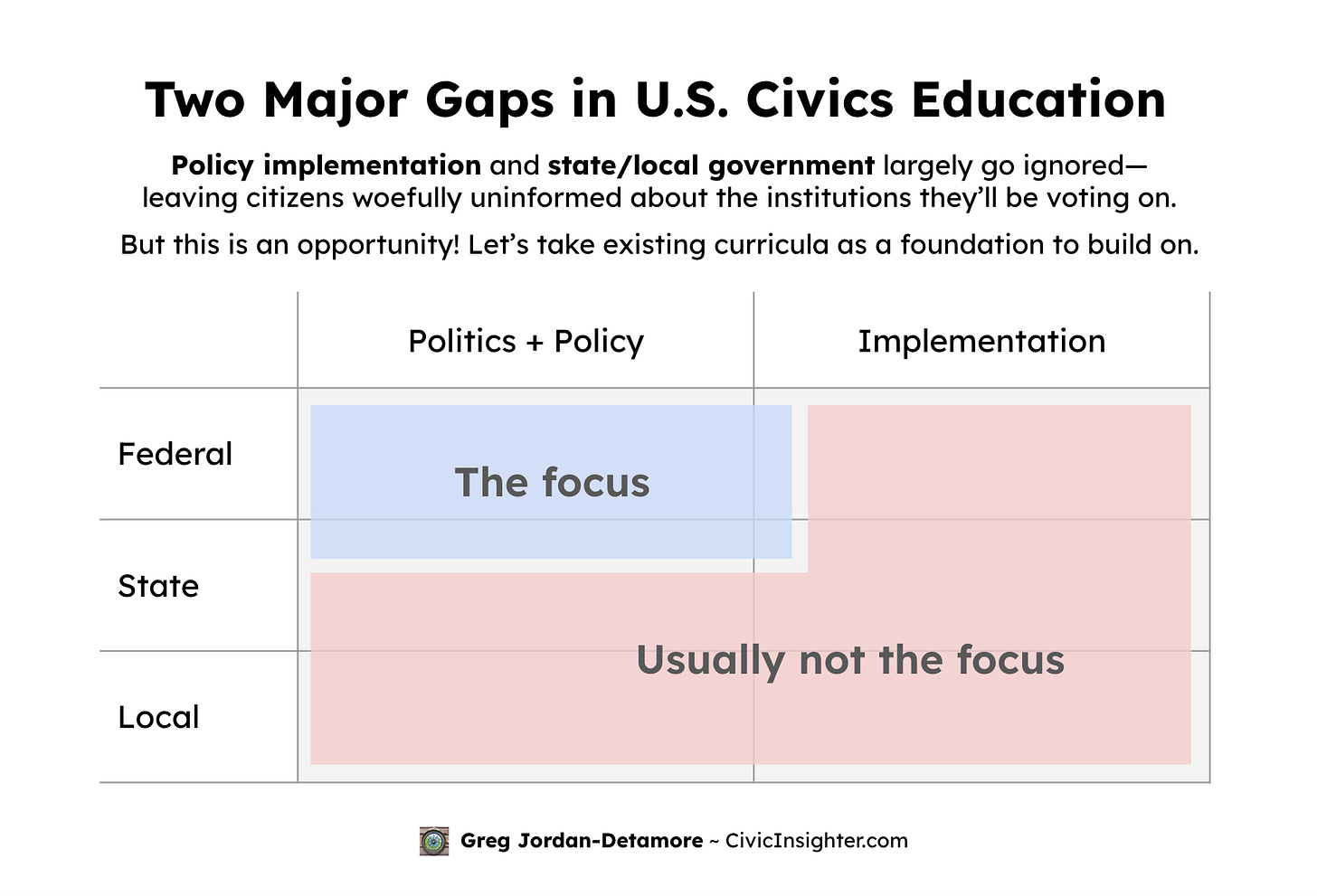

High school is the last time many citizens will receive structured education about how their government works. Unfortunately, U.S. civics education often has two major blind spots: policy implementation and state and local government.

Skipping these leaves future voters with a very distorted view of government.

As the “law of the hammer” says, when your only tool is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. If your civic education is mostly about federal politics and lawmaking, you end up seeing passing new federal laws and executive orders as the primary avenue for action in government.

To explore these issues further, let’s look at the curriculum of AP U.S. Government and Politics as an example, as it’s broadly representative and probably the most widely used.

Gap #1: Implementation—beyond signing bills

When I was in elementary school, our class was shown the classic Schoolhouse Rock video “I’m Just a Bill”:

It’s a cute video! And it’s totally fine for elementary students. But when citizens’ only understanding of government looks like this, you easily get a political culture that obsesses over passing laws then ignores what happens next.

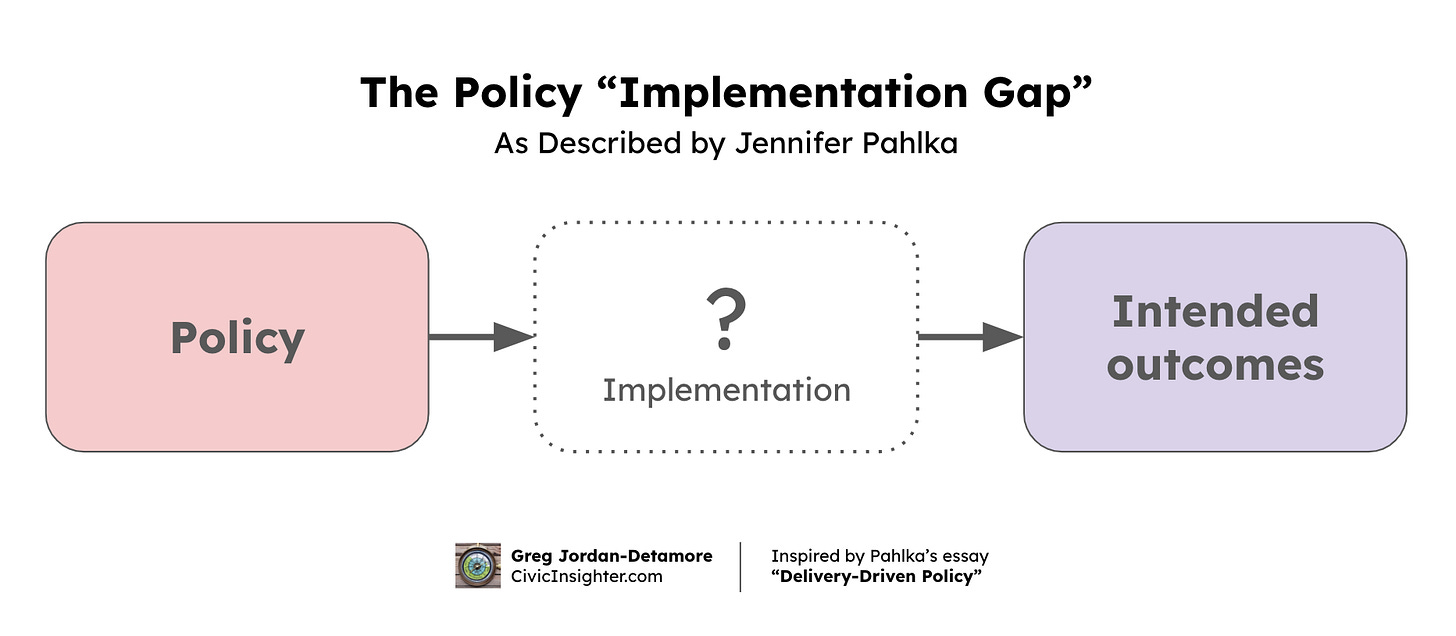

Unfortunately, much of the success or failure of government rides not in the intentions expressed in these bills but in how they get implemented.

The intro to Jennifer Pahlka’s fantastic book Recoding America is appropriately titled: “Beyond Schoolhouse Rock!” She writes:

When the words of a bill become law, they are suddenly magic, or so I believed. But the Schoolhouse Rock! video ended when a bill was passed. What was supposed to happen next was not clear to my preschool brain, but I now understand that somewhere, someone (actually, lots of someones) must figure out how to implement and enforce it. …

It has gotten so difficult to deliver on the promise of legislation that the magic words are losing their magic. Today, when the Schoolhouse Rock! characters cheer our little bill’s becoming law, they are celebrating prematurely.

We talk about signing a bill as if it’s the end of the journey, but in reality it’s just the first step.

You’d barely know it from the way that the bureaucracy is covered in many civics classes. For example, the AP U.S. Government “essential knowledge” regarding “how the bureaucracy carries out the responsibilities of the federal government” is that:

The federal bureaucracy is composed of departments, agencies, commissions, and government corporations that implement policy by:

i. Writing and enforcing regulations

ii. Issuing fines

iii. Testifying before Congress

iv. Forming iron triangles (alliances of congressional committees, bureaucratic agencies, and interest groups that are prominent in specific policy areas)

v. Creating issue networks (temporary coalitions that form to promote a common issue or agenda)

Missing from the list: service delivery.

Whether it’s sending Social Security payments, conducting military operations, maintaining national parks, controlling borders, or investigating financial crimes, the bulk of what government does is service delivery. I find it bizarre for that not to be considered essential knowledge.

Social programs without delivery are merely aspirations.

Criminal laws without enforcement are merely suggestions.

It’s not enough to exclusively focus on politics and policy. Implementation is how promises made become promises kept.

Even at the graduate level, you see this issue in many Master of Public Policy programs:

So, what to do? Every citizen ought to know these things:

Lawmaking ≠ implementation: A law mandating something doesn’t magically make it happen.

Critical resources: Running a government depends on human staff, physical resources (buildings, equipment, infrastructure, etc.), and information resources (data/records, software, telecommunications).

Management: Bringing resources together to accomplish intended outcomes is a complex craft. Success is rarely guaranteed.

Procurement: Governments rely heavily on private companies and nonprofits to execute their missions, with larger contracts typically awarded through formal competitive bidding and smaller (and emergency) spending often more flexible.

High-school students do not need to understand the intricacies of military operations or IT infrastructure migration. But they do need to know that there’s more to government than Schoolhouse Rock—that passing laws is just the beginning.

Gap #2: State and (especially) local government

The curriculum for AP U.S. Government has ~100 pages of required course content yet not a single mention of local government.

Even coverage of state government is mostly limited to the context of federalism—looking at states’ relationship with the federal government rather than as important institutions worthy of their own study.

Meanwhile, of government employees in the U.S., 87% are at the local and state level! Over the past 70 years, federal employment has stayed flat while state and local have exploded:

Number of employees isn’t everything—but it’s safe to say that state and local government are a huge deal.

Funnily enough, students often never learn about how their own school districts work. In other words: Education about government often neglects how education itself is governed.

This creates many problems, including:

Ignorance on key public functions: State and local governments are the primary providers of many things that people see in their daily lives, like education, police, transportation, social services, parks, zoning and building regulations, sanitation, public health, libraries, and more.

Misunderstandings: Local governments are often structured very differently from the federal government, leaving citizens misinformed if trying to use the federal government as an analogy.

Uninformed direct democracy: The place we ask people to exercise direct democracy via ballot initiatives is at the state and local level—precisely the levels many have never learned about.

Nationalization of politics: Teaching students only about the federal government gives the impression that the federal government is the only place for action, which I suspect contributes to our toxic nationalization of politics.

As I’ve written recently, state and local governments offer a lot of opportunities to make an immediate difference in people’s lives:

State and local governments are also trusted much more than the federal government:

And they can even solve problems of intergovernmental coordination on their own:

The variety of state and local governments admittedly presents challenges for teaching, but there’s still a lot we can do, such as:

Common structures: Teach common structures and major variations found in state and local governments nationwide.

Case studies: Use specific states and localities as examples. AP Comparative Government and Politics does this, using China, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia, and the UK as illustrative examples of the range of governments.

Local knowledge: Require learning about students’ own state and local governments.

Debates: Engage students in debates about trade-offs between different governance models.

Some key aspects to examine include:

Elected leadership in the form of a legislature only (which appoints a professional manager to oversee the bureaucracy, as in many cities and counties and in most school districts), a separate executive and legislature (as in all states plus “strong mayor” cities), an executive only (e.g. most sheriffs’ and prosecutors’ offices), etc.

Unicameral vs. bicameral legislatures

Elected vs. appointed judges

Home rule (local autonomy vs. state control)

Distribution of local power between municipalities, counties, and special-purpose districts

Veto powers, including line-item veto

Ballot initiatives

Recall elections

We can debate precisely how much detail is needed—managing expectations for how much high schoolers can realistically be expected to learn—but skipping it all is not the answer.

The U.S. Constitution is exceptionally difficult to amend. But it’s common for voters to be asked about changes to state constitutions or local charters—changes that actually have a chance of happening.

To give credit where it’s due, while the AP curriculum doesn’t include local government (or much about state government) in its 100 pages of required knowledge, it does encourage local civic engagement as one possible applied-learning project.

And there are schools and teachers out there who do try to incorporate state and local content into their civics classes! But it can be really hard without much structural support via standard curricula, textbooks, materials, etc.

Making it happen

It may sound like I’m calling for a radical revision of U.S. civics education, but I actually don’t think that much surgery is needed.

On policy implementation, I don’t think the curriculum needs to go into much detail beyond the few points I listed above. (And as a start, civil service vs. patronage is already a common topic in curricula such as AP.) The big change needed is of messaging: we need to be super clear that passing laws is the beginning, not the end!

On state and local government, a bit more accommodation is needed. I would make room for them by reducing coverage of the following:

Specific U.S. Supreme Court cases covered in detail

Historical evolution of the federal government

Additionally, existing content can be leveraged to help reduce how much accommodation is needed to incorporate state and local government:

Apply federal content: Lessons from the federal government allow much quicker teaching of state and local government—e.g. learning how Congressional committees work greatly helps understand how a city council’s committees work.

Diversify examples of general content: A big part of any civics curriculum is content that transcend levels of government: campaigns and elections, political parties, interest groups, the media, public opinion, etc. Requiring that a spread of federal, state, and local examples be used can help provide state/local coverage without needing more time.

I think civics education is one of the most important things any citizen should get out of high school—after critical thinking, literacy, numeracy, and social skills—so another option is to simply expand civics at the expense of another subject. For example, turning a half-year civics course into a full year, and trimming half a year of something else.

(Note also that by “civics education” I have been referring to education about government and politics. History, civic engagement, civic values, and media literacy are included in many definitions as well, and those topics matter too!)

An equipped citizenry

I graduated high school knowing more about 200-year-old Supreme Court cases than about what a district attorney does, and having read four Shakespeare plays but not a word of the Pennsylvania constitution. That’s not okay.

People graduating high school and going off to (hopefully) be lifelong voters need to be equipped with essential civic education. This includes state and local government—not just federal—and the fact that passing laws is often just the beginning of the work of government, not the end.

This post is not a personal critique of curriculum developers or teachers! To the contrary, I think they have done and continue to do an incredible job of conveying important concepts. Existing civics curricula provide a strong foundation that we have the opportunity to build upon!

I see the status-quo focus on federal politics and policy in education to be just one instance of a larger societal orientation in that direction. But perhaps by changing how we teach, we can push to change the broader conversation.

—

Subscribe for free to hear about my upcoming posts:

Tell me: What changes would you like to see in civics education? How do you think we can make them happen?