Are Public Policy Degrees Too Narrow?

Merging MPPs and MPAs could help fix the gap between policy and implementation.

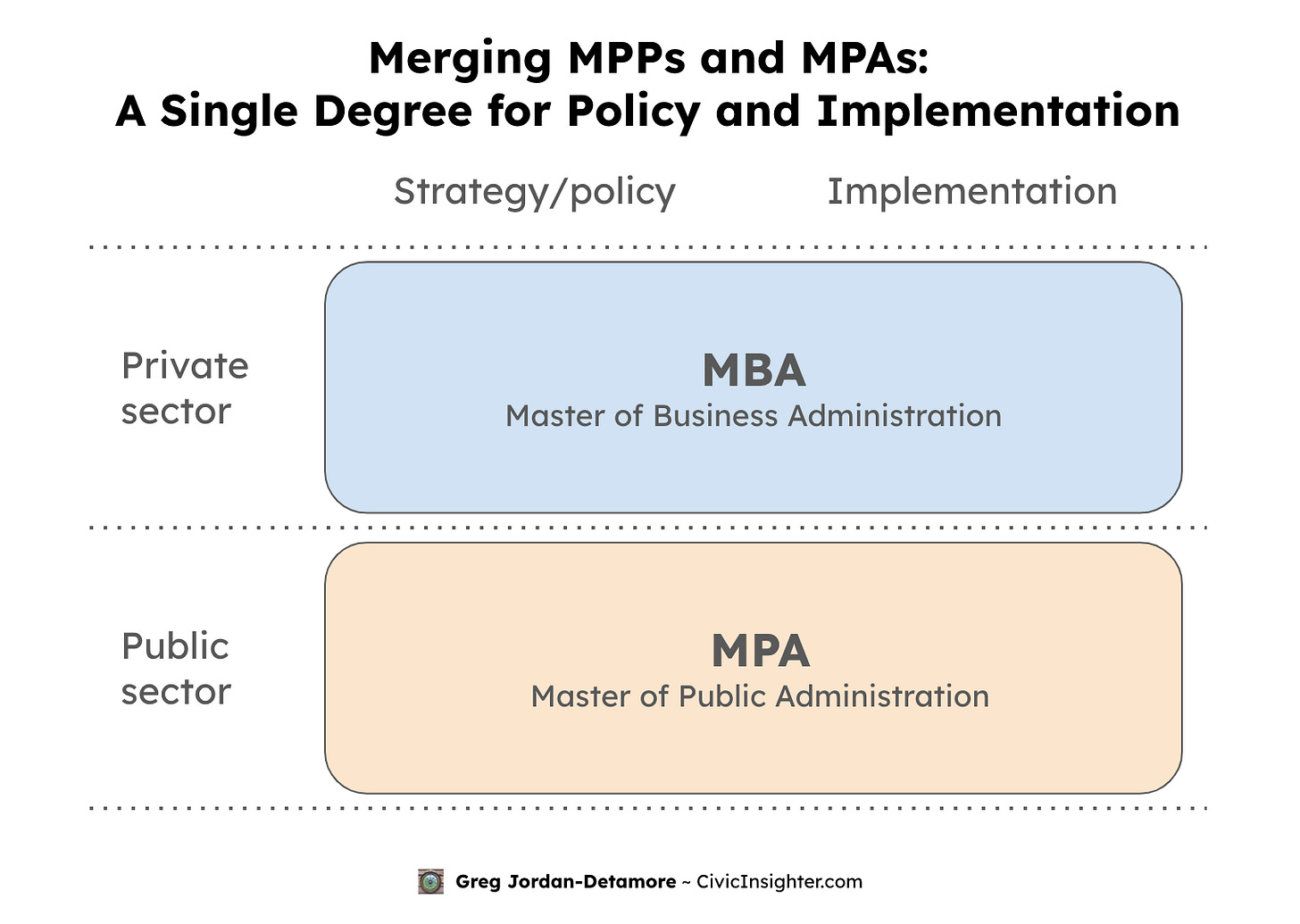

In the U.S., students interested in careers in public service often face a choice between two professional degrees: a Master of Public Policy (MPP) and a Master of Public Administration (MPA).

The difference is that “the MPP degree focuses upon formulating and evaluating public policy while the MPA degree focuses upon the implementation of public policy.”

To help improve service delivery, we should merge these two degrees into one.

Policy and implementation are deeply linked

One of the biggest problems in policymaking today is a lack of attention to how policy will actually get implemented. As Jennifer Pahlka puts it: “The idea that we’re going to create policy over here, and then all the way over there somebody is going to implement it and somehow that’s going to work out well—that’s wrong.” She calls this the implementation gap, and it is a major problem illustrated by numerous examples in her recent book Recoding America.

Successful policymaking requires designing for policy implementation. For example:

If your policy involves civil servants doing anything (most do), you need to be thinking about personnel management.

If your policy involves government buying stuff (most do), you need to be thinking about the mechanics of procurement.

If your policy involves people using websites or software at some point (most do), you need to be thinking about digital technology development.

It doesn’t matter how great your microeconomic analysis or statistical techniques are if you’re making policy that will hit a brick wall when it comes to making a website, hiring staff for a new job role, or changing organizational processes. Many prominent failures of government that we see involve policy being designed without regard for how it will be made a reality.

The flip side matters, too: Students interested in implementation-focused careers need a foundation in policy analysis and program evaluation—as implementation involves making a lot of small-scale policy decisions along the way. And in general, we should be encouraging more back-and-forth communication and ideation, allowing the experience of implementation to inform iterative improvements to policy.

I worry that the MPP vs. MPA degree split encourages a siloed mentality. There is certainly a difference between these two types of job roles, but people filling these jobs are best served with a knowledge of the fundamentals of both, especially given that many people will do both over the course of their career.

MBAs don’t have this separation

Here’s how the topic coverage of MBA programs compares to that of MPP and MPA programs:

And here’s a narrative description of MBAs:

The core courses in an MBA program cover various areas of business administration such as accounting, applied statistics, human resources, business communication, business ethics, business law, strategic management, business strategy, finance, managerial economics, management, entrepreneurship, marketing, supply-chain management, and operations management in a manner most relevant to management analysis and strategy.

Notice how no distinction is drawn between two buckets of study in the way that is done for MPPs and MPAs. It is taken for granted that of course you should cover the full range of topics from strategy and analysis to implementation.

Such a distinction does exist in job roles in the workplace—but the approach is that MBA programs equip their graduates with foundational knowledge and skills across the board, no matter which future path they take, as you need to see the full picture to play your part.

Merging the MPP and MPA

I would combine the MPP and MPA into a Master of Public Policy and Administration—or even more simply just a Master of Public Administration, mirroring the name format of the MBA.

Beyond the name

Despite all the grand pronouncements about how different MPP and MPA programs theoretically are, in practice there’s often a lot of overlap. And a few universities already offer a “public administration and policy” degree.

Also, many universities offer only an MPA or an MPP but not both, which can create internal pressure to offer a wide range of courses that turns into something like what I’m suggesting, despite the degree name. Fun fact: In New York State, offering an MPP is illegal!1

So having a single degree is not radical.

Names aside, it’s also critical to think about the substance of the programs. A few subjects come to mind that ought to be a bigger focus:

Procurement: How government buys goods and services is one of the most under-appreciated drivers of success or failure.

Digital technology: We live in the digital age, and there’s hardly a function of government that doesn’t depend on databases, websites, and software.

Design: Service design, content design, user experience, visual design. But also architecture and interior design; buildings often play a key role in service delivery.

Communications: Both overall communications strategies and specific messaging/language can have a big impact on people’s behavior.

Personnel: It would be great to see a particular focus on improvement and reform of hiring processes (how can we make it not take a year to hire someone?), retention efforts, promotion and job-change policies, and more.

I haven’t said “X number of credit hours” or “require a course with X title” because there can be multiple approaches—both through dedicated courses and woven in with existing content—and I’d love to see different ones tried!

Case study: Policy implementation for MPP students

At Harvard’s Kennedy School, which offers MPPs and MPAs2, Nick Sinai is one of several instructors who teaches a core course on policy implementation for MPP students. In an excellent post, he describes the course:

This spring (2023), each instructor was given a bit more latitude, and so I focused the class on government service delivery and issues of digital government. Topics included user-centered design, prototyping, product management, ethics, risk management, budgeting, metrics, communications, and more.

Students partnered with clients from real government agencies.

Despite the challenges of trying to incorporate some elements of a field class at scale, each student team found creative ways to research human needs, build and test prototypes with real people, and understand the complexity and constraints of government execution. They then delivered a strong presentation and implementation plan for their client.

Reflecting on the course, Sinai writes:

In the business world … most business schools require a course in business strategy, but they also teach management, operations, marketing, entrepreneurship, etc. Similarly, a school of government should of course teach policy, but it should also teach management, operations, public-sector entrepreneurship, etc. Strategy and Policy are about what an organization can and ought to do, but the questions of how to do it are just as worthy of a subject in a graduate school like HKS. Execution matters.

I find this example inspiring and would love to see more of this kind of material woven into MPP/MPA programs.3

Recap

The proposal here is to merge MPPs and MPAs into a single degree, just like what already exists in the case of MBAs, in order to improve the connection between policymaking and implementation. Furthermore, regardless of what degree names are used—and even if existing separate MPP programs are maintained—more attention needs to be given to key issues in improving 21st-century service delivery.

There’s a lot to say about undergraduate education too, but that’s beyond the scope of this post. Stay tuned.

Subscribe to hear about my next post, which is related to this topic—but with a spicier take. 🔥

What do you think? Is this a step in the right direction? Are there things I’m missing or getting wrong? Have you done an MPP or MPA program? Let me know in the comments!

Update

Continuing this conversation, four posts of note have been published since this one:

Emily Tavoulareas: On Policy Schools: The gap between policy and implementation has roots in academia

Jennifer Pahlka: Will academia buy policy-delivery fusion?

Me: Meet the MBPA: Master of Business and Public Administration

The New York state government regulates which degree titles universities are allowed to offer, and an MPP is not one of them. As such, MPAs in New York often have a curriculum spanning the full range of public policy and administration. The results are sometimes funny, such as Cornell’s Public Policy school not offering any degrees in “public policy”—only public administration and health administration.

Harvard is exploring a plan to merge its MPP and MPA programs, according to an April 2023 article. It’s unclear to me how much of this merger is due to the kinds issues I mentioned here vs. some of the particulars of their situation; their MPA appears to be a “take whatever you want” program with no core curriculum, whereas about half the MPP consists of a common core.

For another example, check out Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age.

Nice article! I am currently writing a manuscript on Human Service Organizations and I am grappling with several questions regarding the scope of various degrees that train individuals to work in the public sector.

I recently read McGuinness and Schank's book _Power to the Public_ on this idea of Public Interest Technologies. I am curious how your ideas fit with theirs.

Love this! Early in my career, I saw the same dichotomy between high-minded policy folks and administrators grinding it out in the trenches. I calibrated my own Masters from American University to split the MPA/MPP degree programs - but could only wish for course offerings like Professor Sinai’s. I think inclusive methodologies like HCD/co-design should actually be mandatory for public administration degree programs in this day and age.

I’d like to share one additional aspiration - maybe something you can expand on in a future post - that American MPA programs expand offerings beyond traditional New Public Management (NPM) approaches. NPM, in my view, pairs well with neoliberal economics and policies. But I personally wish I could find more coursework and intellectual leadership aligned with University College London (UCL) Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, which is developing tools and capabilities for co-creating and co-shaping markets instead of teaching established tools for fixing market failures.