Civil-Service Flexibility: Empower Managers, Not Politicians

We can create more flexibility in government hiring without returning to the spoils system. The key: empowering civil-servant managers.

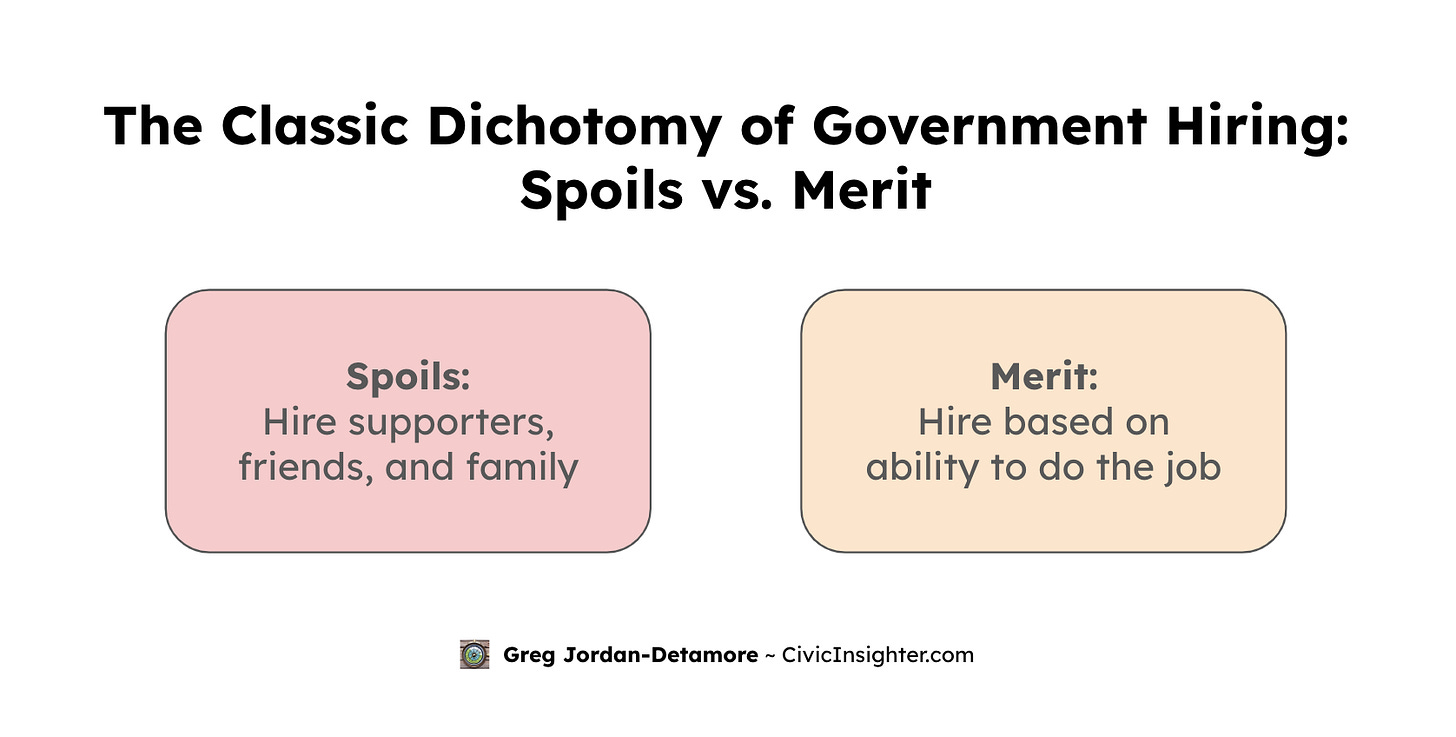

Government jobs are often framed as a dichotomy between two systems:

Spoils (patronage) system: “a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward for working toward victory, and as an incentive to keep working for the party”

Merit system: “the process of promoting and hiring government employees based on their ability to perform a job, rather than on their political connections”

The principles of the merit system are great! But many people—including many civil servants—feel that it often doesn’t work as well as intended, for a range of reasons, including:

Long, complex hiring processes that often drive qualified candidates to choose jobs elsewhere or to not apply in the first place

Difficulty promoting high performers

Difficulty removing low performers

The topic has become more salient in the U.S. recently due to President Trump’s wish to revive the “Schedule F” system, which would allow the President to strip certain federal jobs of their civil-service protections. It’s a bad idea and is not serious civil-service reform.

Another way?

Could there be some way to create more flexibility while embracing the principles of the merit system?

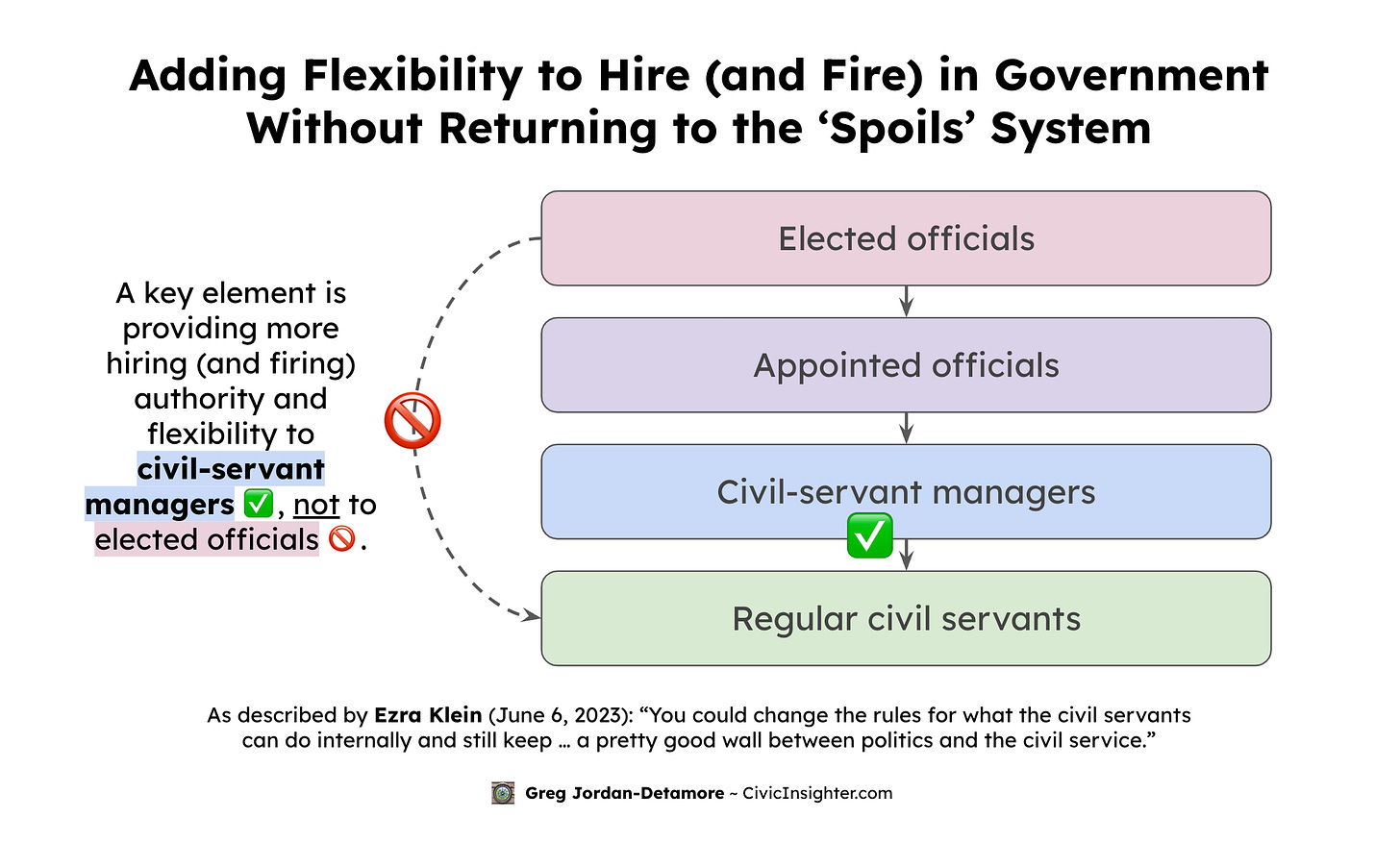

In a podcast last year, Ezra Klein made an interesting and important distinction:

I think people go too quickly to the idea that if you created a lot more autonomy and flexibility within the civil service, made it easier to hire, easier to fire, that has to mean it’s easier for the political system to hire and fire, which I do think is something we should be at least a bit careful with.

Whereas, I’m talking really about the ability of the civil service to hire and fire internally unto itself, which is a different question already because they’re just different rules. That’s why in Schedule F, Trump is trying to move people from civil to political. But you could change the rules for what the civil servants can do internally and still keep—I think maybe you do want less wall than you currently have, but a pretty good wall between politics and the civil service.

In graphic form:

I think he framed things beautifully and have been thinking about it ever since.

In a recent podcast (“In This House, We’re Angry When Government Fails”), he had two guests talking about hiring.

Jennifer Pahlka described the current federal hiring process:

You have a system that is supposed to hire people on the basis of merit. But when you interpret that very, very, very rigidly, what you do is say: OK, we don’t want to have people involved in selecting candidates who aren’t familiar with all the ways in which we try to reduce or eliminate, really, bias in the process. And so what we’ll do to hire civil servants is we will have human resources people screen their resumes and look for—and I’m not kidding you—exact matches in the language between the job description and what’s on their résumé.

Because that’s—if you’re taking things very literally—an indicator that they have the exact, right skills for the job. And then once you’ve found all the people who were great at cutting and pasting, then you send them all a self-assessment questionnaire. Because it’s safer to have them self-assess than it is to have, say, if it’s a programming job, have programmers interview them—where they might bring their own biases to the table.

And then you’ve down-selected twice on the basis of their ability to copy and paste, and then essentially lie about their skills. Because if you don’t put “master” on every single level of the self-assessment, you don’t make it to the next cut. And then we apply veterans preference, and that’s the certification that gets handed to the hiring managers.

And that is not consistent with merit. You really are then hiring people just who know how to work the system. That process that I just described, where we rely entirely on self-assessments, is how 90% of competitive jobs are done in federal government. 90% we do not assess independently.

She noted:

If you use judgment, somebody can criticize your judgment. If your process has no judgment in it, what is there to criticize?

Things haven’t always been this way everywhere. The other interviewee, Steven Teles (who wrote a phenomenal essay, “Kludgeocracy in America”), noted:

My dad entered into NASA in the 1960s, and this was an agency that actually had a lot of what political scientists called bureaucratic autonomy. It had a lot of ability to organize itself, to hire, to fire on the basis of very high standards for performance.

Over time, things can get off track. He continued:

Things go wrong. There’s a scandal. We add a new process, we add a new procedure—without really thinking about how it interacts with all the rest of it. And so we shouldn’t necessarily think that the problems that Jen is describing are a result of the fact that anybody designed this thing to operate this way.

It’s really the result of just additional layers of accretion without corresponding layers of destruction.

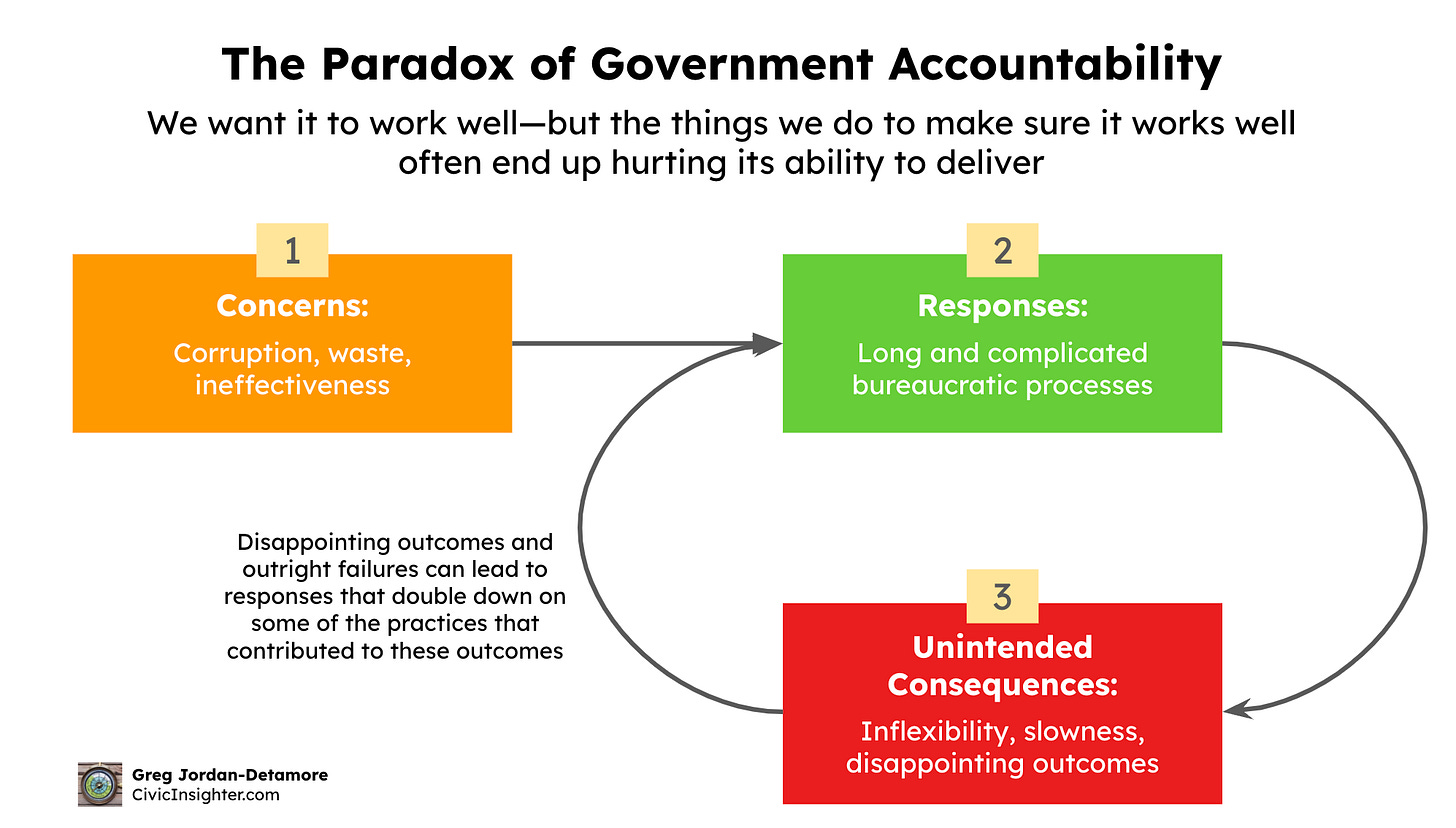

This ties into a previous post I wrote about how a lot of things that we do to try to make government better end up making it worse:

Well-intentioned policies and procedures that try to address legitimate concerns about corruption, waste, or ineffectiveness end up creating new problems:

And that brings us to a lot of the problems we have today.

There’s a lot to be said about improving hiring and management of the civil service at every level of government—and countless people are working on it, with some exciting developments!

I just want to underscore Ezra’s point: Flexibility in hiring and managing civil servants ≠ political control or a return to the spoils system. The key is giving flexibility to civil-servant managers, not elected officials.

I’ve got upcoming posts on improving government forms, observations from vacation in Baghdad, hidden problems with ranked-choice voting, and innovations in municipal governance. Subscribe to get them straight to your inbox!

Can you think of any specific examples of where it would be helpful to have more flexibility and autonomy for civil servants to hire and manage others? Let me know in the comments!

Hi Greg, interesting post as usual! One question I have about this is how would an increased flexibility of civil servant managers to hire (and more importantly fire) interact with union representation?

This is quite interesting!

Not something I ever thought about, thanks for sharing :)