Designing Better Services with Industrial Engineering

The fields of service design and industrial engineering tackle many of the same problems. What if they joined forces?

Suppose you’re looking to design a more seamless end-to-end experience for patients at a health clinic, or reduce the amount of time that people spend waiting for government permits, or improve operations and customer satisfaction at Disneyworld.

Who would you hire to help you out?

There’s a funny situation: There are (at least) two different professions focused on this—and as far as I can tell, they have very little contact with each other.

One is “concerned with the optimization of complex processes, systems, or organizations by developing, improving and implementing integrated systems of people, money, knowledge, information and equipment.”

The other focuses on “planning and arranging people, infrastructure, communication and material components of a service in order to improve its quality, and the interaction between the service provider and its users.”

These are Wikipedia’s definitions for the fields of industrial engineering and service design. They’re not identical, but the similarities are striking.

Service design’s focus is fairly obvious: the design of services. But the name “industrial engineering” can be confusing, as it’s not what many people think of when they hear the words “industrial” or “engineering”; it’s not about designing factory machines.1 In fact, it’s not about physical products at all—it’s about processes, systems, services, and workflows. It might be better to pair or even replace it with “operations engineering,” “management science,” or “service engineering,” and indeed you can find those terms in use.2

Adding to the confusion is the similar-sounding field of industrial design, which is not super related industrial engineering. Industrial design is about the design of physical products, whereas industrial engineering is explicitly not focused on that.

Both service design and industrial engineering look at improving both the internal operations of an organization and the experience of the people they serve, with the former usually driving the latter. And both involve detailed analysis of existing conditions to information possible avenues for action.

They came from different places but ended up focusing on similar things. As I understand it, here’s how they evolved:

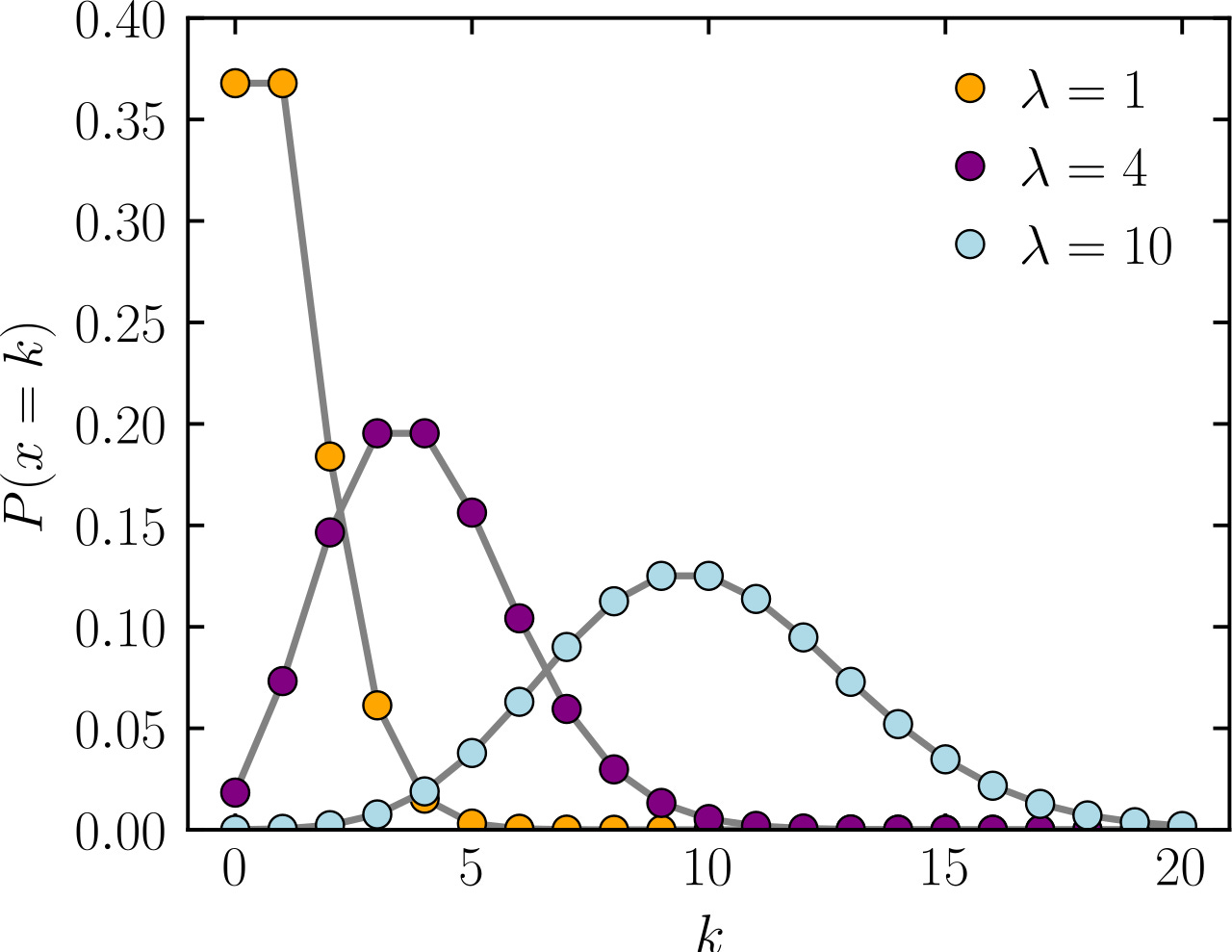

Industrial engineering emerged from traditional engineering, asking if engineering approaches could be applied to processes too, not just physical stuff. Initially this was manufacturing processes, but now a large part of it is focused on human-facing services. Industrial engineers tend to have a background in engineering, either having competed a dedicated program in industrial engineering or having transitioned from another branch of engineering. Research methods tend to be quantitative.

Service design emerged from asking if methods of product design could be applied to services too, applying principles and practices of design thinking and human-centered design to the scale of entire services. Service designers tend to have a background in design—these days often digital product design, but sometimes in physical product design, graphic design, or other areas. Research methods (arguably) tend to skew qualitative, though it can vary.

Let’s see what they have to offer each other.

Why service design needs industrial engineering

Industrial engineering adds two key pieces of value to service design: a quantitative focus and subject-matter expertise on operational issues.

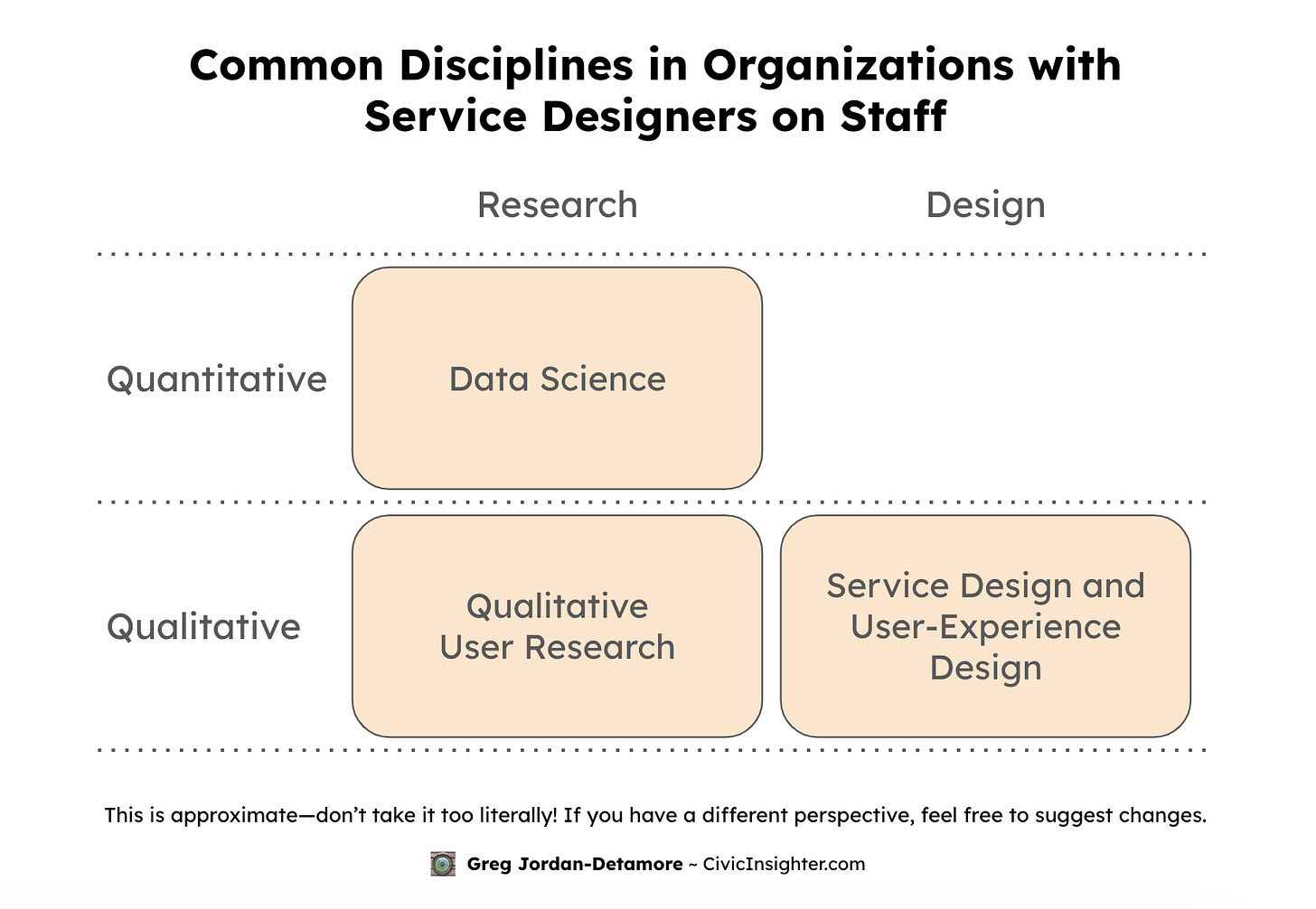

In my experience, the types of teams and departments that employ service designers often have staff in these disciplines:

An important part of any design work is first doing research. A lot of service designers personally have a background that is more rooted in qualitative research, though some do have a mixed-methods (qualitative and quantitative) background, and others work together with data scientists. But certainly when it comes to the actual design side of things, my experience has been that service design tends to be overwhelmingly qualitative. It seems that there’s often a gap on the quantitative side.

Including more math has a lot of value to add to help take (already amazing!) service-design work to the next level. As basic example: If you’re reimagining how services and processes might be improved, quantities like money and time aren’t just implementation details—they make a high-level difference between whether something is viable or not.

Industrial engineering takes a much more quantitative approach, one that can be helpful to create more well-rounded design solutions. It can help fill in the gap that I showed above, in a manner something like this:

The second major attribute that industrial engineering offers—specifically its key sub-field of operations research—is subject-matter expertise on operational and managerial issues.

A lot of the researchers and designers who work in the service-design space used to work in other subject domains. Product designers have expertise in both design principles and their specific physical or digital product domain. Data scientists have a methodological foundation plus (often) specific knowledge and experience with health data, political data, environmental data, or whatever.

Organizational management and operations is its own subject domain, and operations researchers and industrial engineers have been producing a rich research literature on it for decades.

Let’s say you’re looking to improve wait times for a particular service. Data scientists and qualitative researchers from any subject background can definitely provide value in trying to unpack the causes for wait times! But did you know that operations researchers have a specific field of study focused on precisely this problem?

Industrial engineers and operations researchers usually have training on a number of subjects relevant to operations and management, such as:

Modeling, analysis, and optimization of processes and workflows

Economics and finance

Human factors and ergonomics

Layout of physical facilities

Production control

Logistics and supply-chain management

People with a background in these operational and managerial issues can be very useful for looking at service delivery. (Of course there’s also value to including people whose subject background is elsewhere, to bring in new ideas and avoid groupthink.)

Why industrial engineering needs service design

Industrial engineering has been around for a lot longer than service design. It can be tempting to look at service designers and say, “They’re just the new kids on the block, reinventing something with a new name yet without much mathematical rigor” but I don’t think that’s fair.

Companies and governments have been in the business of serving people forever—yet the principles and practices of human-centered design have made enormous positive improvements to our world over the past couple decades.

Qualitative research can be really helpful in learning about the human nuances of services and processes, and makes a great addition to the quantitative work that is often the focus of industrial engineering.

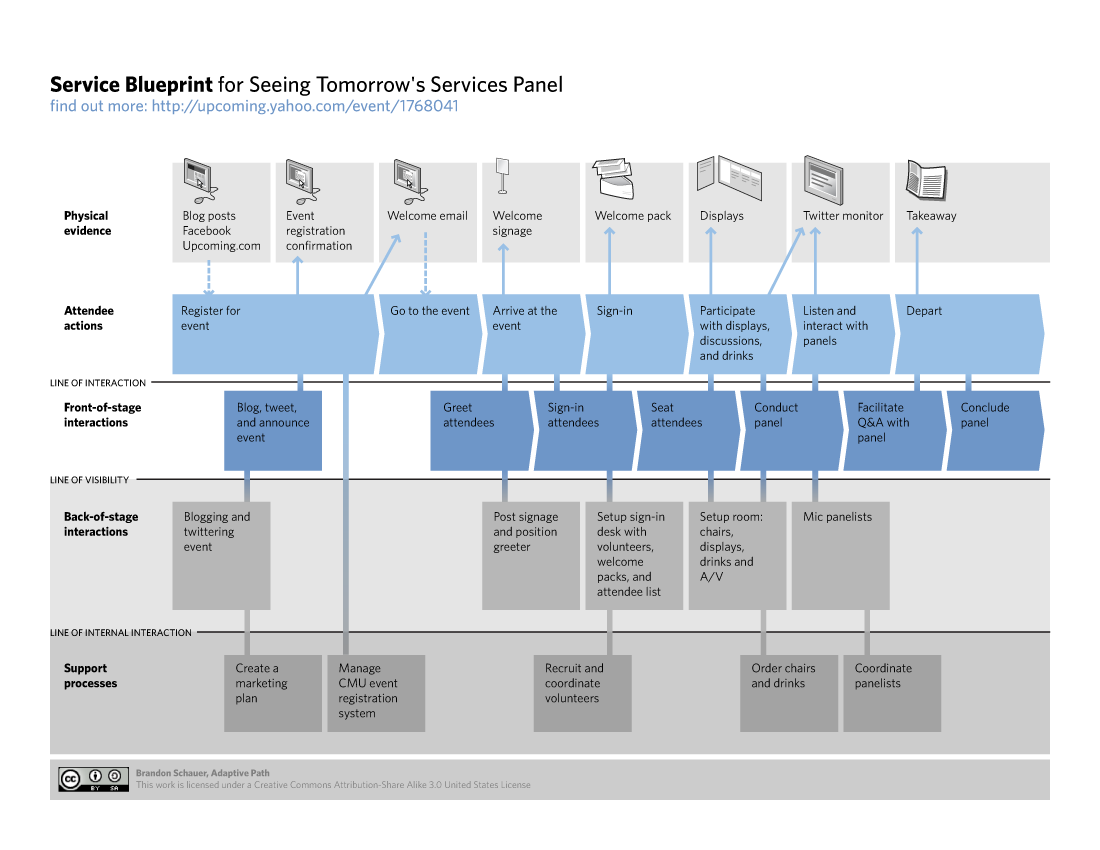

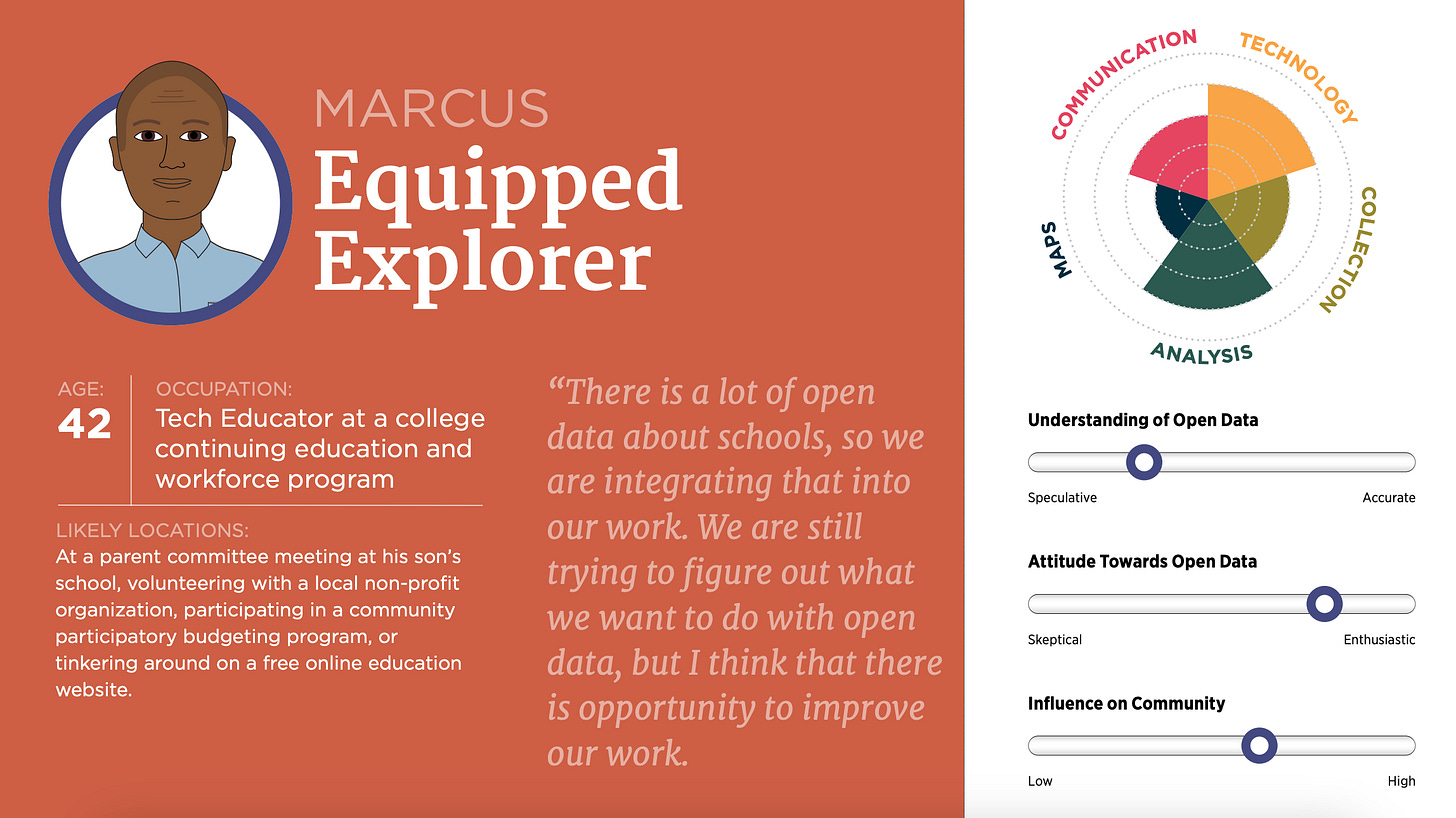

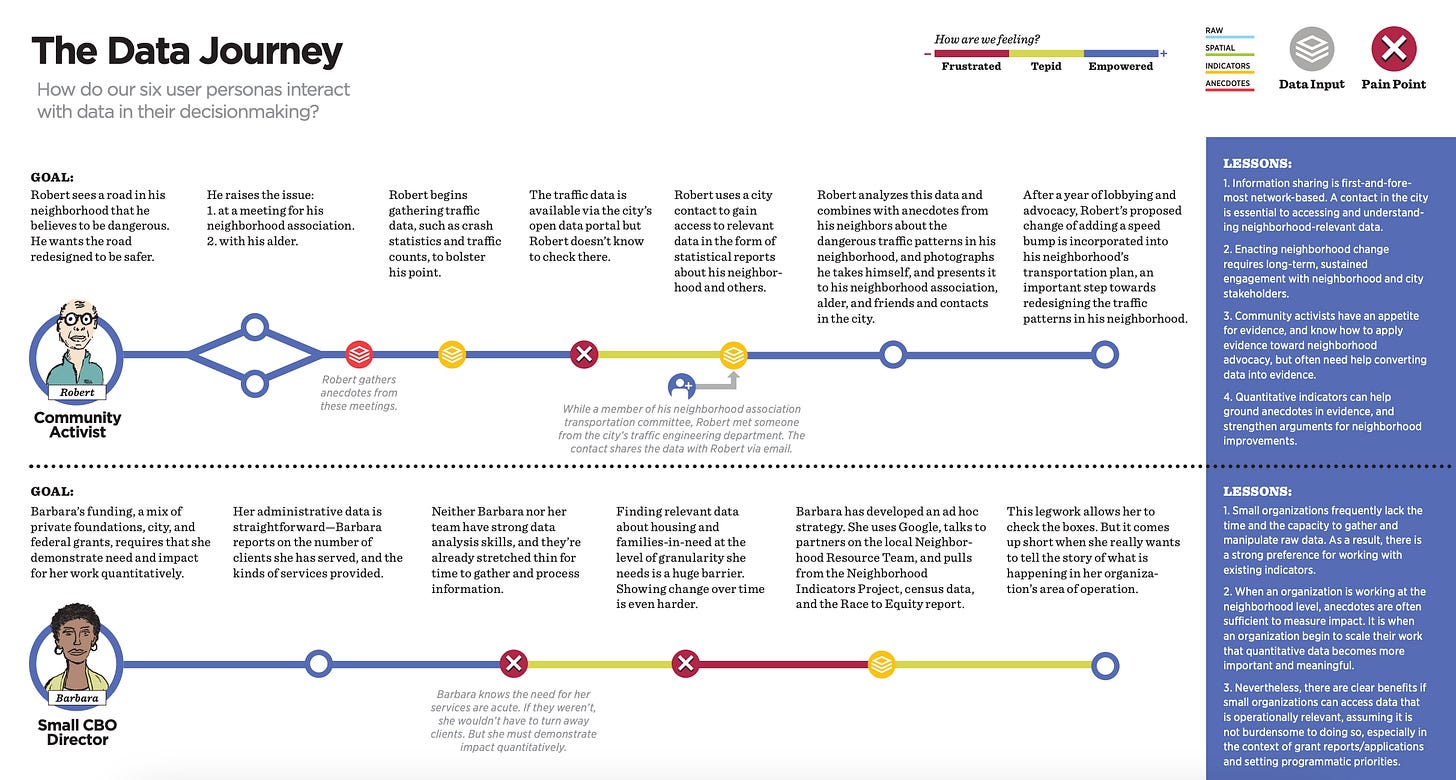

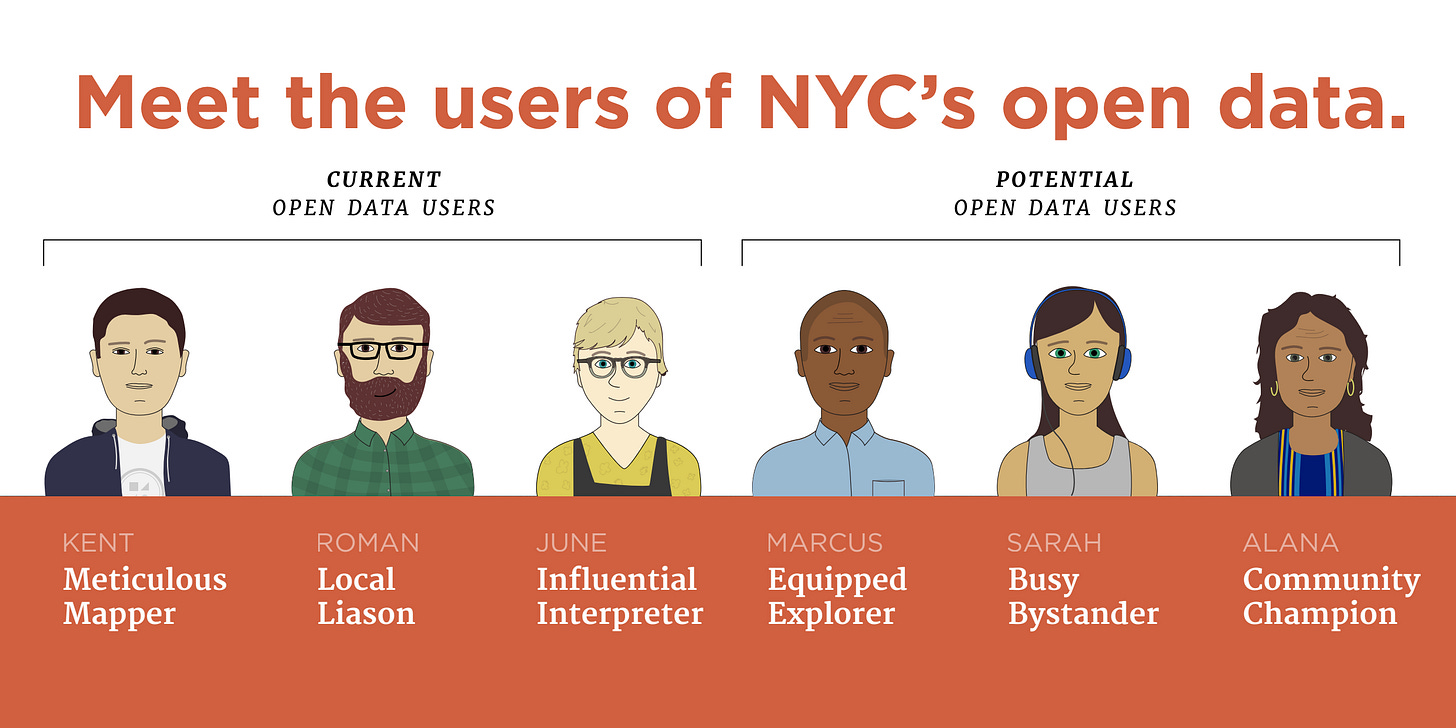

It’s easy to get lost in the spreadsheets and mathematical models and operational analysis. The types of work that user researchers and service designers do—and particularly the artifacts they create, like user personas and journey maps—can do an incredible job of really putting a human face on things and help people remember and prioritize the goal that we’re trying to deliver on in the first place: serving people.

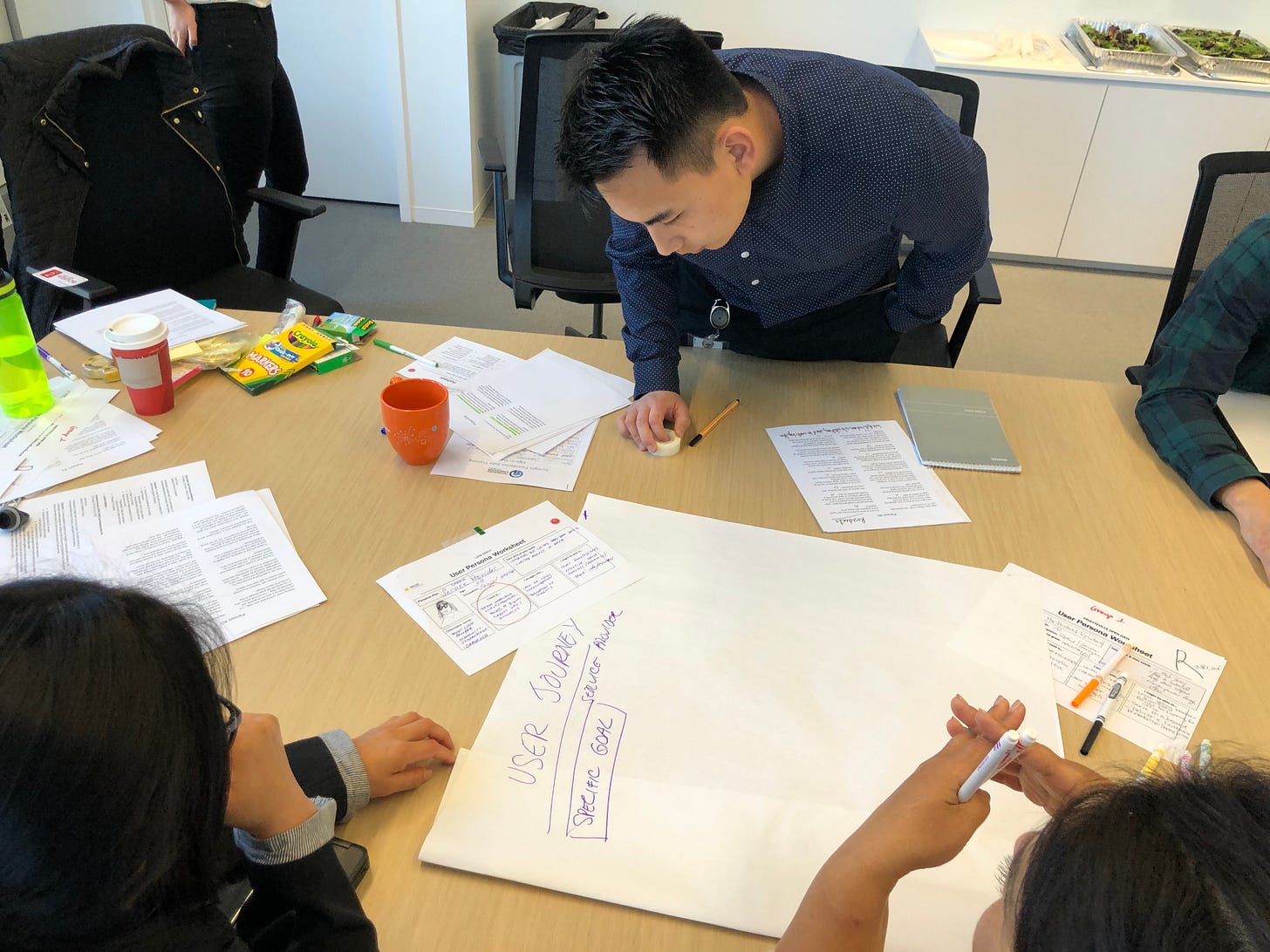

I have taught many workshops on human-centered design and personally witnessed the kinds of “aha!” moments that people have when introduced to these kinds of concepts and methods. This stuff can make a big difference!

Better together

This isn’t an issue of one being better than the other. Both fields have a lot of value, and could be an enormous complement to each other—creating an opportunity to increase impact!

A joint area of work might be defined as: Analysis, planning, design, and optimization of processes and systems of human, physical, and information resources to deliver a quality service to end users.

Perhaps you call it “service engineering” (there’s a book with that title), perhaps “service design and operations engineering,” perhaps something else.3

Here are some concrete things that can be done:

Interaction: Service designers and industrial engineers should talk to each other more and read about each other’s work.

Teams: Organizations should build teams that bring together people from both of these backgrounds, and provide professional development in the areas of each other’s skills.

Education: Universities and other institutions should offer programs that combine the two—aiming to create people who can bridge the gap. (Of course there will always be a role for people who specialize in just one side of things.)

There’s a lot more to say on this issue, so I’ve got some upcoming posts in the works, including:

Details on what a joint curriculum could look like

Thoughts on how this might be incorporated in government and policymaking

A closer look at how service design was originally intended to have a more quantitative side

A comparison of job descriptions for service designers vs. industrial engineers

Make sure to subscribe to find out when they’re published!

Can you think of any opportunities for increasing impact by bringing these approaches together? Are there other related fields that you also think are relevant to include here? Let me know in the comments.

Another unfortunately-named field is environmental graphic design—which is not about “the environment” as we think of the term today, but rather the environments around us; it focuses on things like wayfinding signage. It has come to be replaced with “experiential graphic design.” Similarly, Harvard had a “Visual and Environmental Studies” department, which was recently renamed to “Art, Film, and Visual Studies.”

For example, the University of Michigan has a department of Industrial and Operations Engineering, and Stanford’s engineering school has a department of Management Science and Engineering. Many universities have departments of “Industrial and Systems Engineering”; “Industrial Engineering and Operations Research” is also a common name. You can also find these terms in use beyond academia. Note that systems engineering often has more of a focus on physical systems (mechanical and electrical), not just processes.

I’m not necessarily arguing whether they should “merge into one field” or not, as that seems like an endless philosophical discussion. Is industrial and systems engineering one field or a combination of two fields—or actually just a sub-field, or pair of sub-fields, of the larger field of engineering? And is service design a field by itself, or a sub-field of design? I’ll go with “a joint area of work.”

Love it! This post brings a couple related ideas to mind.

Something we witness in our work is that the people performing the tasks that originate from service design and/or industrial engineering (service blueprints, business process models, etc.) tend to have very different backgrounds (and sometimes no formal training in either discipline).

In practice, you can get any number of people to follow the methodology to produce a journey map, etc. but the fidelity of the work depends a lot on the individual's training and experience (e.g. to focus on the right problems, ask the right questions, recognize bias and blind spots, get authentic responses in interviews, etc.). The methodology mainly serves to yield a recognizable output. The individuals (and how they attend to different facets of a problem) largely control what insights and recommendations can be drawn from the outputs.

I tend to see a lot of attention to decisions about what activities to do (journey maps, etc.) and not as much to decisions about *who* performs them. Organizations tend to simply match a role to a task, without going deeper. This is maybe because service designers advertise themselves as "universal" researchers, who can work on any problem. In more mature disciplines, it's recognized that the title of a role is not sufficient. For example, in software, organizations recognize that their in-house developers don't necessarily know how write embedded software. The developers can count on their training to be able to *learn* how to do it, but they wouldn't claim to be able to do it *today*. In service design, I haven't yet seen this sort of specialization come up as a consideration.

Bringing things back to your post, related to the above, your post distinguishes two common backgrounds for people working in this area, and how that background can bias what they pay attention to, and what conclusions they tend to draw.